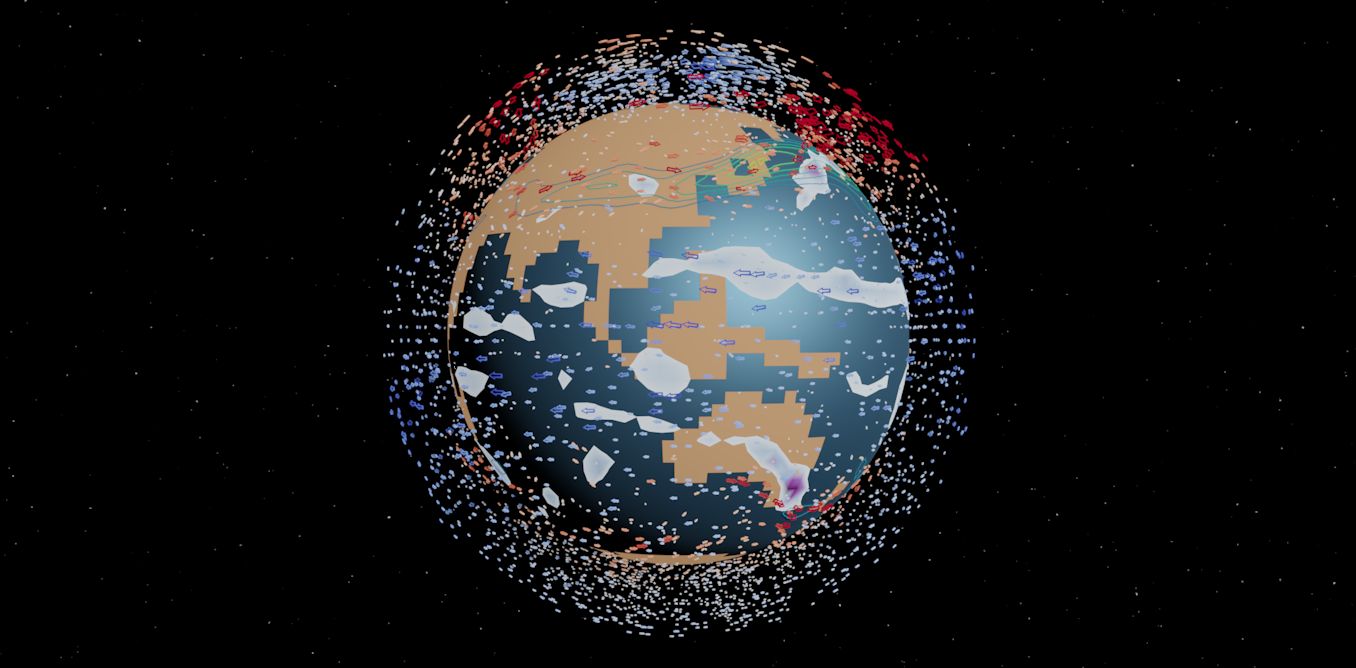

A more realistic depiction of clouds and aerosols appears to explain why a new generation of climate models indicate the world is more sensitive to rising CO2 levels John Gilbey / Alamy

Climatologists have been trying to figure out why new computer models have started projecting a potentially much warmer future as CO2 levels rise. New analysis gives our best guess yet – it appears to have to do with clouds.

In front of upcoming major UN Climate Science Panel reports in 2021the researchers found their sixth generation of climate models show a much wider range of future temperatures than before, ranging from 1.5-4.5°C to 1.8-5.6°C. These estimates relate to when “equilibrium climate sensitivity” (ECS) occurs, a theoretical point where the climate system equilibrates after CO2 levels have doubled.

“There is certainly no single common cause. But many of the higher end models have introduced new, more sophisticated cloud and aerosol patterns. This seems to be driving the new higher sensitivity,” says Catherine Senior of the UK Met Office.

The results imply that climate sensitivity – global warming based on a given increase in CO2 – is higher than previously thought. A more realistic representation of clouds and aerosols appear to be the likely reason, according to Gerald Meehl of the US National Center for Atmospheric Research and colleagues, who reviewed 37 of the new models.

Higher climate sensitivity – as measured here by the ECS, although there are other approaches – is important because it implies a smaller “carbon budget”, the amount of CO2 that humanity can emit without triggering very dangerous warming.

Older models assumed that the water in supercooled clouds, much of which is found in the Southern Ocean, was ice, which would have a cooling effect on climate. Now, thanks to better understanding due to aircraft observations, water is treated as a liquid despite being below freezing, which removes some or all of its cooling effect.

“It’s definitely more physically realistic,” says Bill Collins of the University of Reading in the UK, who was not involved in the study. However, he cautions that the question of how well climate models can estimate climate sensitivity remains open.

Steven Sherwood of the University of New South Wales, Australia, who was not a member of the research team, says many climate scientists are “alarmed” by new models showing greater climate sensitivity. However, he notes that some models predict lower sensitivity, which means the reality is a greater spread of possible warming outcomes.

“Decision-making must live with the current level of uncertainty and must consider the possibility of very high sensitivity and terrible outcomes if we don’t manage substantial and rapid emission reductions,” he says.

Journal reference: Scientists progressDOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba1981

Learn more about these topics: