Many recent climate models have predicted disastrous global changes. The problem is that climate forecasters are currently ignoring decades of scientific best practices that would provide more accurate predictions.

Fortunately, there are attempts to rectify the truly questionable methodology that has been used to make 21st century climate predictions.

A significant new climate paper published in Nature Climate Change, written by Viktoria Eyring of the University of Bremen and 28 co-authors from around the world, does just that.

It is really necessary. Here’s why:

Meteorologists know that certain models work better than others in specific situations, and they tend to rely on the versions that work best, depending on the forecasting problem. When the problem is potential heavy snow along the east coast, forecasters usually rely on the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting model (the “Euro” model). When diagnosing changes in jet stream patterns a week or 10 days ahead, they can give more weight to the US model of the global forecast system.

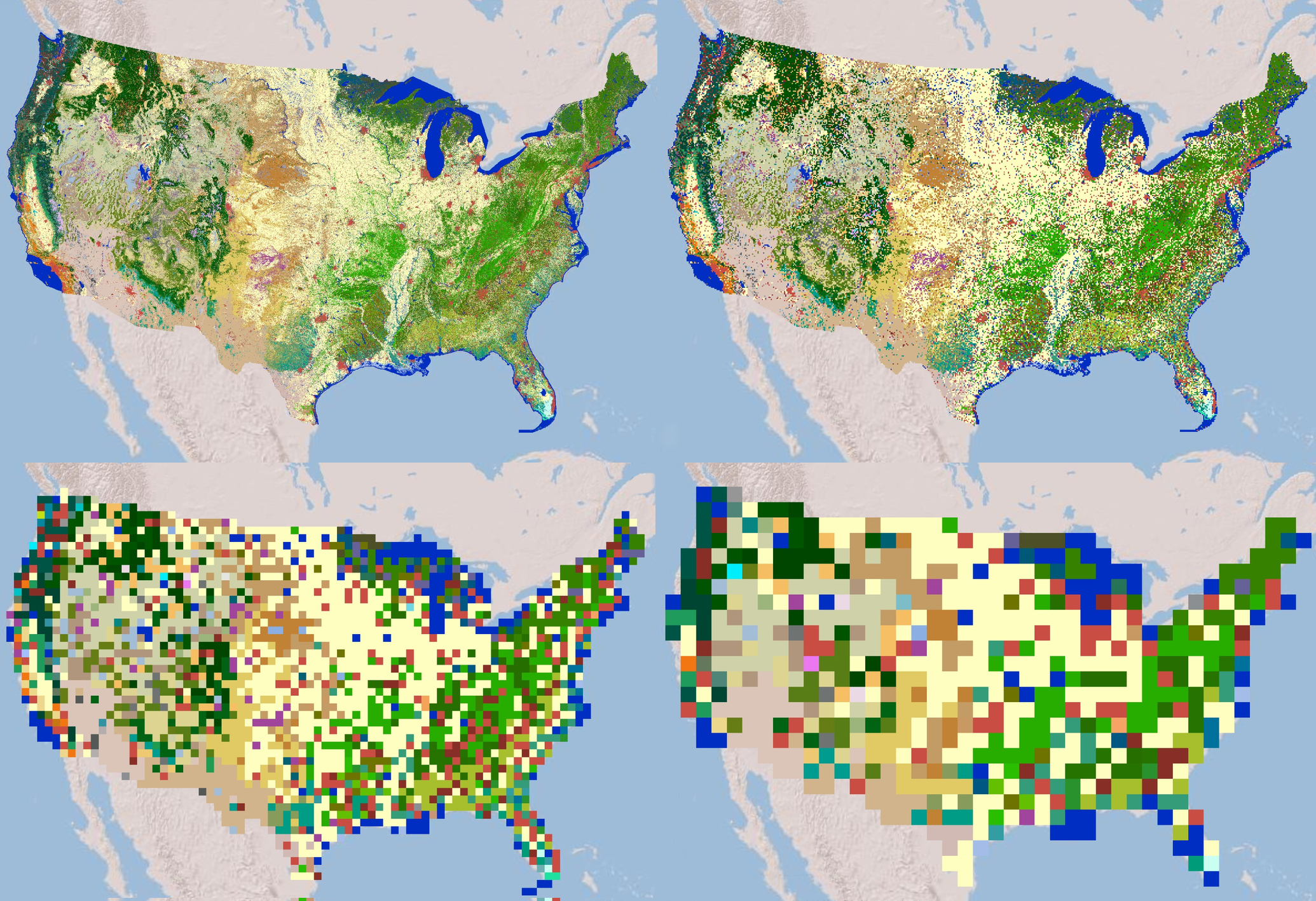

But the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change simply averages 29 major climate models to predict 21st-century warming, a practice rarely used in operational weather forecasting. As Eyring and others have dryly noted, “it is now proven that giving equal weight to every available model projection is suboptimal”.

In effect. The authors of the new paper show that aggregate models make huge mistakes in three of the places on earth that are critical to our understanding of climate.

The first big mistake concerns the entire Southern Ocean, the huge body of circumpolar water separating South America, Africa and Australia from Antarctica. All 29 models calculate, on average, that it’s significantly less cold than it actually is, with broad bands of 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit or warmer than reality. Since the southern margin of the Southern Ocean is mostly sea ice, this means that large areas of real-world ice are simulated as liquid water.

Additionally, almost all of the moisture that precipitates over Antarctica comes from the Southern Ocean, and a huge amount of additional water vapor in the forecast comes from the practice of using models that raise the temperature of the ocean a few degrees above what it actually is. The result is a forecast of non-existent snow masses from an ocean with non-existent open water areas.

Another significant error is along the west coast of South America. In the real world, thanks to the constant pull of the trade winds that push water away from the coast, cold groundwater springs up. When, for largely unknown reasons, the trade winds momentarily weaken, the surface water temperature rises dramatically, inducing a El Nino that can cause flooding thousands of miles away in Southern California.

In a world experiencing a modest warming trend, El Niño typically produces record high temperatures. The model also greatly underestimates a similar area of upwelling off the African coast that induces the tropical Atlantic version of El Niño, known as the Atlantic Nino.

There is a current theory that some of the heat from each El Niño is retained in the atmosphere and temperatures do not return to their previous value once an El Niño goes away. As a result, surface temperatures seem to jump with every fat. Climate models that significantly underestimate natural cold water upwelling tend to create El Niño-like conditions, which may explain their tendency to predict too much global warming.

But one of the models actually works. According to John Christy and his colleagues at the University of Alabama, only the Russian model, designated INM-CM4, is successful. So why not weigh heavily on the model that works? Maybe because it contains less global warming than all other UN models?

His successor, INM-CM5is so good that it alone diagnoses the warming “pause” from 2002 to 2014. That the “pause” was real is evident in the global context. surface temperature recording the one on which the IPCC relies the most, from the University of East Anglia’s Climate Research Unit.

It’s high time the scientific community came clean about long-standing climate shenanigans. Averaging a large number of models that do not perform well is guaranteed to produce an unreliable forecast. Using those that get it right, like the two Russian models, is an accepted best practice in weather forecasting. When it comes to forecasting methodology, new research brings climate science at least closer to the 20th century.

Patrick J. Michaels is director of the Center for the Study of Science at the Cato Institute.