Climatologists use mathematical models to project Earth’s future in a warming world, but a group of latest models included surprisingly high values for a measure called “climate sensitivity.”

Climate sensitivity refers to the relationship between changes in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and warming.

High values are a bad surprise. If they’re right, that means a warmer future than expected – warming of up to 7℃ for Australia by 2100 if emissions continue to rise unabated.

Read more: There are no time-traveling climatologists: why we use climate models

Our recent study analyzes these climatic models (called CMIP6), which were published at the end of last year, and what information they give for Australia.

These models contain the latest improvements and innovations from some of the world’s leading climate modeling institutes and will feed into the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report in 2021.

But the new climate sensitivity values raise the question of whether previous climate modeling has underestimated potential climate change and its effects, or whether the new models are exaggerating.

If the high estimate is correct, it would require the world to make deeper and more urgent emissions cuts to meet a given warming goal.

Shutterstock

What is climate sensitivity?

Climate sensitivity is one of the most important drivers of climate change, strongly influencing our planning for adaptation and mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions.

Read more: Explained: what is climate sensitivity?

It is a standardized measure of the response of the climate when the concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere double. There are a few indices of climate sensitivity used by the scientific community, and perhaps the most commonly used is “equilibrium climate sensitivity”.

We can estimate equilibrium climate sensitivity by sharply increasing carbon dioxide concentrations in models and then calculating the warming experienced after 150 years – when the atmosphere and ocean would return to temperature equilibrium.

In other words, give the climate a “boost” with more carbon emissions and wait for it to settle into a new state.

The previous generation of models (CMIP5) had equilibrium climate sensitivity values between 2.1℃ and 4.7℃ of global temperature change. The values of the latest models (CMIP6) range from 1.8℃ to 5.6℃.

This includes a group of models with a sensitivity of 5℃ or more, a group of models in the previous range, and two models with very low values at around 2℃.

What this means for our future

Higher equilibrium climate sensitivity values mean a warmer than expected future climate, for any given scenario of future emissions.

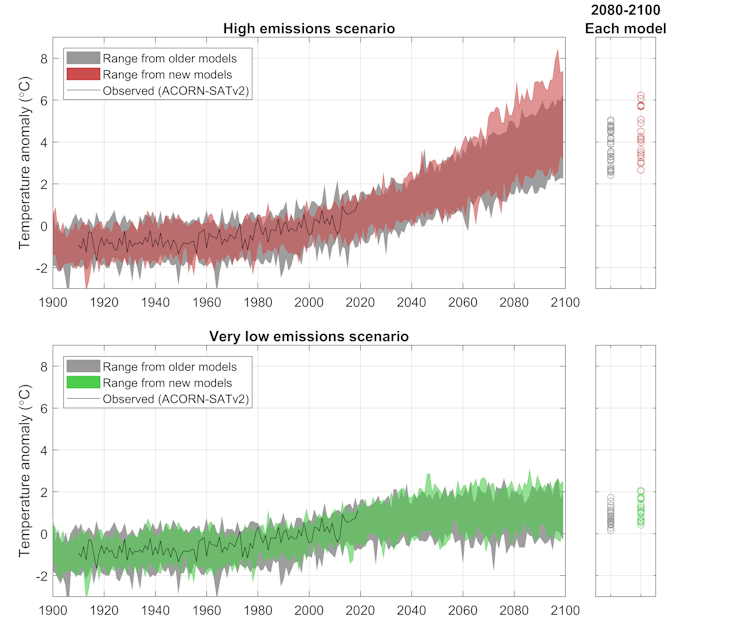

Author provided

According to these new models, Australian warming could reach more than 7℃ by 2100 under a scenario where greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase over the century.

These higher temperature changes are not currently shown in the national climate projections, as they did not occur in the previous generation of emissions models and scenarios.

So what does this mean in practice?

Higher climate sensitivity means increased temperature extremes. This would mean that we would see greater changes in other climate characteristics, such as extreme rainfall, sea level rise, extreme heat waves and more, reducing our ability to adapt.

Read more: Eliminating fossil fuels now could keep warming below 1.5°C

High equilibrium climate sensitivity would also mean that we need to further reduce our greenhouse gas emissions for a given global warming target. The Paris Agreement aims to keep global warming well below 2℃ since pre-industrial times.

Should we be worried?

They are credible models, representing next-generation versions of the most successful modeling systems, developed over decades at top research institutes globally. Their findings cannot be dismissed out of hand simply because we don’t like the answer.

But – we shouldn’t jump on this piece of evidence, dismiss all the others, and assume that results from a subset of new models are the final answer.

Read more: Why 2℃ of global warming is much worse for Australia than 1.5℃

The weight and credibility of each piece of evidence must be carefully assessed by the research community and by the scientists preparing the next IPCC assessment.

We are only just beginning to understand the reasons for the high sensitivity of these models, for example how clouds interact with particles in the air.

And there is other evidence that underpins the IPCC estimate of equilibrium climate sensitivity.

These include observed warming since the last ice age about 20,000 years ago; measurements of the warming observed over the last decades from the greenhouse gases already emitted; and understand the different climate feedbacks from field experiments and observed natural variability. These other data sources may not support the results of the new model.

Read more: We climate scientists won’t know exactly how the crisis will unfold until it’s too late

Essentially the jury is still out on the exact value of equilibrium climate sensitivity, high values cannot be excluded, and the results of new models should be taken seriously.

In any case, the new values are a disturbing possibility that no one wants, but that we still have to grapple with. As researchers in a to study conclude: “what scares us is not only the models [equilibrium climate sensitivity] is wrong […] but that it might be right”.