[ad_1]

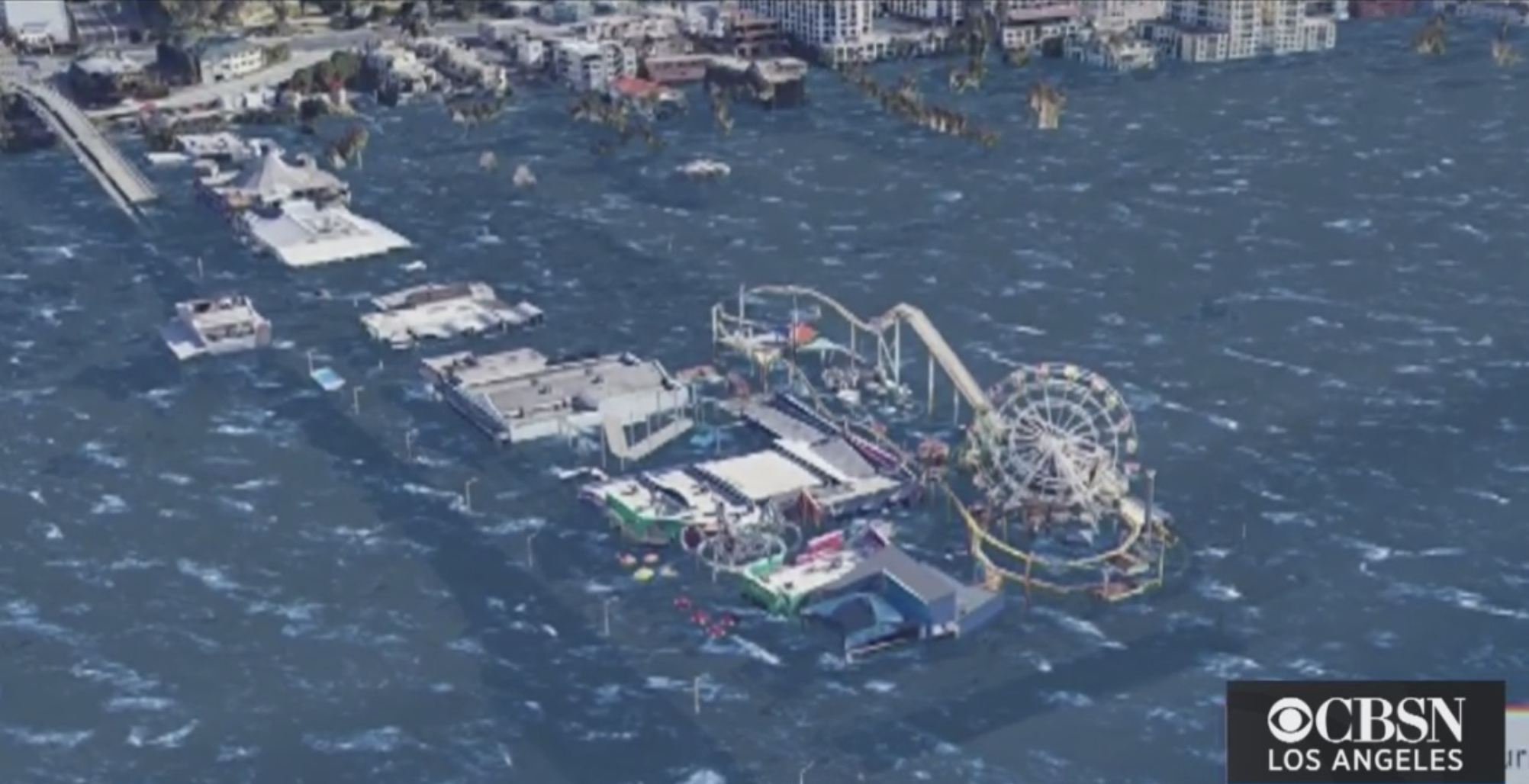

From thermal domes in the Pacific Northwest to flooding in Henan, China, 2021 has been a year of extreme weather events. It is more crucial and more timely than ever to identify the appropriate means to tackle climate change.

With the conclusion of climate talks at the United Nations General Assembly, the eyes of the world are on the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), the results of which will be critical for the global climate future .

Decisions made at the conference will, in part, be based on findings from scientific papers using so-called “Integrated Assessment Models†(IAM), which “combines different streams of knowledge to model human society alongside parts of the Earth systemâ€.

Existing AIMs have integrated economic, technological and biophysical processes that produce greenhouse gas emissions. While politics plays an important role in shaping climate-related policies and trajectories, political scientists have not been actively involved in the development of integrated assessment models and, by extension, the scientific basis for it. climate policy development. This must – and can – change.

The missing contribution of political science to climate modeling is probably due to two main factors: the lack of exposure and meaningful interaction between political scientists and climatologists and a great difficulty in modeling political phenomena. Indeed, when I was a doctoral student at Stanford taking classes in climate modeling in 2017, I was told to be the first from political science to do so.

While some have already expressed concern about the unrealistic representation of the model, actual design and implementation to address these concerns has been scarce. After all, this is a very difficult and time-consuming task, requiring at a minimum an intimate knowledge of the political world, familiarity with the models and knowledge of what can be incorporated, as well as the technical expertise to bring to bear. artwork.

I think political scientists can help model the climate in specific areas. My recently published exercise, which conceptualizes and implements the internalization of a key political concept – human security – offers lessons on how to achieve this.

Making reasonable assumptions about political behavior can provide essential information about future alternative climates. A critical step towards achieving this goal is to conceptualize and quantify fundamental political science ideas such as power, violence and preferences so that they can be incorporated into IAMs. Not all basic ideas lend themselves to incorporation, but some recently published econometric studies – which “transform theoretical economic models into useful tools for economic policy making” according to the International Monetary Fund – leading the way. I postulate that political scientists have a lot to contribute to answering two fundamental questions.

First, what would be optimal? Political scientists can improve the estimation of the optimal carbon price – the price at which the net social benefit of carbon emissions would be maximized – by internalizing the costs of significant social impacts not previously taken into account.

One example is the cost of climate-induced violence. My recent study uses econometric estimates of the costs of human violence and the climate-violence relationship and an established model called MERGE. He thinks that such internalization can significantly influence the optimal carbon price. The impact can be significant and sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to be the biggest beneficiary in terms of avoiding damage from climate-induced violence. As future researchers adjust the approach taken in the study, they may incorporate other missing, but potentially significant, social damages. A promising candidate could be that of climate-induced migration.

Second, what would be feasible? Climate policies concern distributive policy, so tThe second axis is to introduce and adjust the representation of political constraints in the MOIs according to constituency preferences, incumbent’s electoral incentives, incumbent’s ideology or partisan orientation, and the presence of powerful interest groups, among other factors.

In democracies, voters would support climate policy if they believe it is in their best interests and oppose it otherwise. However, voters’ preferences are not taken into account in the same way by career-conscious incumbents who, when eligible for re-election, would pursue the set of policies likely to maximize their electoral results. In addition, governments tend to place more importance on the well-being of a nucleus of citizens than on opposing groups and would be more inclined to adapt to the preferences of powerful interest groups. A modeling goal would be to represent these considerations to achieve a workable set of alternatives.

While none of this is easy, integrating political science into climate modeling is meaningful and long overdue. As statistician George Box said once, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” Political scientists can help make climate models more real and useful and contribute more substantially to climate policy making.

Dr Shiran Victoria Shen is a political scientist and environmental engineer, Hoover National Fellow and Assistant Professor at the University of Virginia.

[ad_2]