Designing climate experiments is nearly impossible in the real world. We cannot, for example, study the effects of clouds by removing all the clouds for a set period of time and seeing what happens.

Instead, we have to design our experiments virtually, by developing computational models. Now a new open-source set of climate models has allowed this research to become more collaborative, efficient and reliable.

Read more: Why scientists adjust temperature readings and how you can too

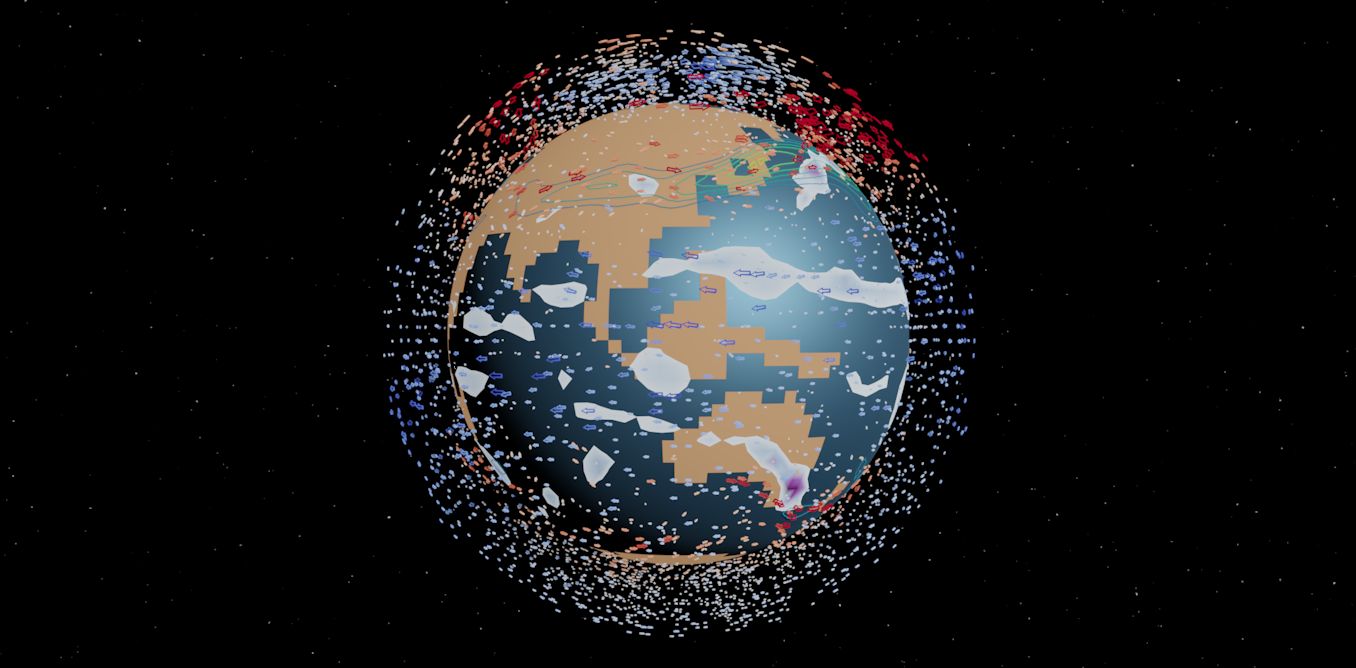

Full climate models are designed to be as close to nature as possible. They are representations of the combined knowledge of climate science and are arguably the best tools for understanding what the future might look like.

However, many research projects focus on small parts of the climate, such as sudden changes in wind, temperature in a given region, or ocean currents. For these studies, focusing on a small detail in a comprehensive climate model is like trying to find a needle in a haystack.

It is therefore common in such cases to remove the haystack using simpler climate models. Scientists usually write these models for specific projects. A quote commonly attributed to Albert Einstein perhaps best sums up the process: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

Here is an example. In an article from last year I observed temperature and wind changes in the upper atmosphere near the equator. I didn’t need to know what happened in the ocean, and I didn’t need chemistry, polar ice, or even clouds in my model. So I wrote a much simpler model without those ingredients. It is called “MiMA” (Mmodel of a Itreaty Moist Aatmosphere), and is available for free on the Web.

The disadvantages of simpler models

Of course, using simpler models has its own problems.

The main problem is that researchers need to be very clear about the limitations of each model. For example, it would be difficult to study thunderstorms with a model that does not reproduce clouds.

The second problem is that while the scientific results may be published, the code itself usually is not. Everyone must believe that the model does what the author claims, and trust that there are no errors in the code.

The third problem with simpler models is that anyone else trying to duplicate or rely on published work would have to reconstruct a similar model themselves. But since the two models will be written by two (or more) different people, it’s highly unlikely that they’ll be exactly the same. Also, the time that the first author spends building his model is then spent a second time by a second author, to best achieve the same result. It’s very inefficient.

Open source climate models

To remedy some (if not all) of these problems, some colleagues and I have builds a framework of climate models called Isca. Isca contains easy-to-obtain templates that are completely free, documented, and come with software for easy installation and execution. All changes are documented and can be undone. Therefore, it is easy for everyone to use the exact same templates.

The time it would take for everyone to build their own version of the same model can now be used to extend existing models. More pairs of eyes on a model means errors can be quickly identified and corrected. The time saved could also be used to create new analysis software, capable of extracting new information from existing simulations.

As a result, climate models and the resulting science experiments become both more flexible and more reliable. All of this only works because the code is publicly available and because any changes are continuously tracked and documented.

An example is my own code, MiMA, which is part of Isca. I was amazed at the extent of research for which it is used. I wrote it to study the tropical upper atmosphere, but others have since used it to study the life cycle of weather systems, the Indian monsoon, the effect of volcanic eruptions on climate, etc. And this is only a year after its first publication.

Read more: Climate models too complicated? Here’s one that anyone can use

Making templates freely available in this way has another benefit. Using accessible evidence can counter the mistrust of climate science that still prevails in some quarters.

The burden of proof automatically falls on the skeptics. Since all the code is there and all changes are traceable, it’s up to them to point out errors. And if someone finds a mistake, that’s even better! Fixing it is just one more step to make the models even more reliable.

Going open source with scientific code has a lot more pros than cons. It allows collaboration between people who do not even know each other. And, more importantly, it will make our climate models more flexible, more reliable, and generally more useful.