Most people have a fairly clear position on human-induced climate change, even though the vast majority of people don’t know much about the scientific basis of the climate models used to study it. It’s understandable – they are indeed very complicated and not accessible to everyone.

In a sense, it doesn’t matter if climate models are only understood by climate modellers, as long as they can interpret the results of their research for others to understand. But that leaves them open to the suggestion that their research is somehow ‘inferior’ to that of scientists who don’t use models – despite the fact that models are used in every field of science, from economics to science. ‘astrophysics.

The essence of science is to model our world, it follows that understanding the underlying model is key to understanding predictions and its uncertainties.

Model the world

The advanced climate models on which groups such as Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change their climate projections are developed from the models used in weather forecasts. Weather models mainly deal with questions such as “where does the wind come from?” and “is it going to rain?”

These are essentially questions about how the atmosphere will circulate in the next few days. This is why these types of models are called “general circulation models” (GCMs). When extrapolating climate, we basically use longer term forecasts of the same.

Today’s GCMs are probably the most complex and advanced scientific models ever created. But their complexity also makes them difficult for the general public to understand, making them less likely to trust model predictions. To the general public (and even others in the climate research community), these GCMs are essentially black boxes – you put something in (like increased CO₂ concentration) and you get a response (the warming of temperatures).

These answers might be easier for the audience to understand if we take a step back from the more complex models and instead use one that is easier to understand. There’s no better way to learn than by doing, so my lab has designed a climate model that people can try out for themselves.

A simplified climate model

A simpler approach to climate modeling is often based on the first law of thermodynamics: the conservation of energy. It models how energy enters or leaves the system and thus models the energy balance of the earth’s surface. These models are called “energy balance” models.

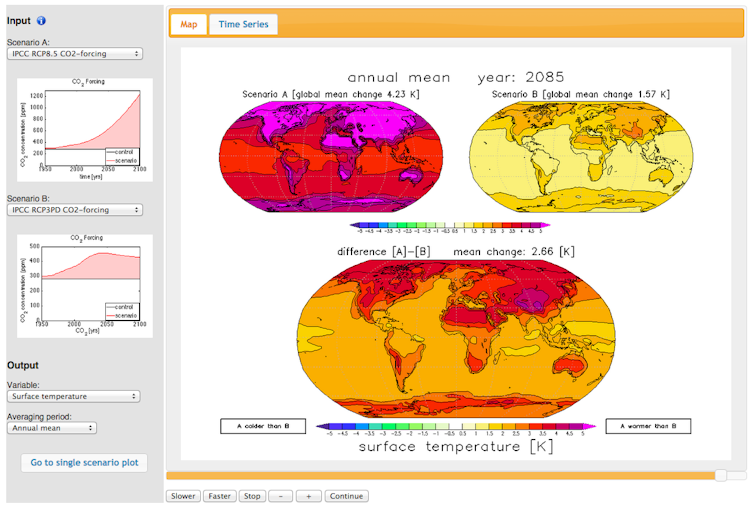

New Simple Monash Climate Model (MSCM), which my research team developed, allows students and the public to use an actual climate model to make their own climate simulations. It provides a simple model of the average global climate and its response to external factors such as changes in sunlight or CO₂ concentration.

The MSCM allows you to study the results of over 2,000 different model experiments interactively. You can take the special climateand see how it reacts to different climate change scenarios. It also provides educational tutorials on climate, climate models and climate change, and even some fun puzzles.

virtual worlds

Experimental simulations are a key method in science. They allow you to address “what if?” questions that are not easily answered simply by observing the real world or by experiencing it.

Using our model, you can, for example, answer the question of what would happen if you [took away all clouds](http://monash.edu/research/simple-climate-model/mscm/greb/cgi-bin/dmc_i18n.py?activetab=undefined&version=Basic&locale=EN&atmosphere=1&clouds=1&co2=1&heat_diff=1&heat_adv=1&albedo=1&hydro=1&vapour_diff =1&vapour_adv=1&ocean=1&model=0&atmosphere_s=1&clouds_s=0&co2_s=1&heat_diff_s=1&heat_adv_s=1&albedo_s=1&hydro_s=1&vapour_diff_s=1&vapour_adv_s=1&ocean_s=1&model_s=0&lat=&lon=®ions=0&location=Global%2%2). the role of clouds in the climate system unless we see what happens when they’re not there?

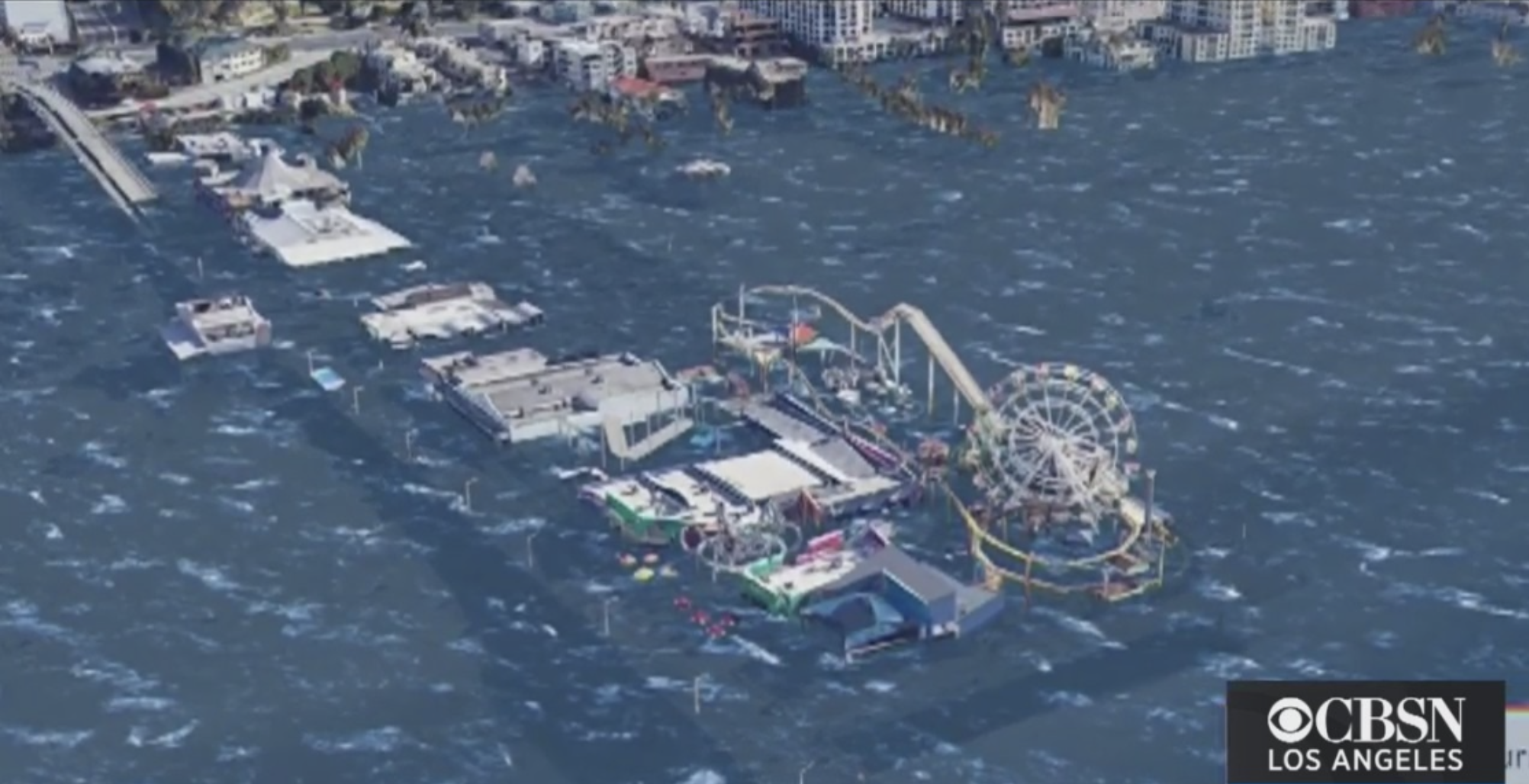

Just as some people scoff at modeling as “not real science”, we only have one Earth and one climate, so we can’t do “real” experiments with it. By using models, we can test important questions such as what would happen if we doubles the concentration of CO₂ in the atmosphere. In fact, this may not be the best example, as we are well on our way to experiencing this in real life – although the models should hopefully warn us of the impacts in time for us were avoiding the real thing.

Speaking of the future, a publicly available climate model could also be used in schools, helping to equip future generations with a better understanding of our climate system. For a generation growing up in a rapidly changing climate, this will educate the public about what lies ahead and could also inspire the next generation of scientific modelers – in climate as well as in many other scientific fields.