[ad_1]

Earth’s climate system is interconnected and complex, and even small changes in temperature can have big impacts

With the United Nations climate conference in Scotland shining a light on climate change policies and the impact of global warming, it helps to understand what the science is showing.

I am an atmospheric scientist who has worked on global climate science and assessments for most of my career. Here are six things you need to know, in graphical form.

What drives climate change

The main focus of the negotiations is carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that is released when fossil fuels – coal, oil and natural gas – are burned, as well as by forest fires, land use changes. land and natural sources.

The industrial revolution of the late 1800s sparked a huge increase in the burning of fossil fuels. It powered homes, industries, and opened the planet to travel. That same century, scientists identified the potential of carbon dioxide to raise global temperatures, which at the time was seen as a possible benefit to the planet. Systematic measurements began in the mid-1900s and have shown a steady increase in carbon dioxide, the majority of which is directly attributable to the burning of fossil fuels.

Once in the atmosphere, carbon dioxide tends to stay there for a very long time. Some of the carbon dioxide released by human activities is taken up by plants, and some is taken up directly in the ocean, but about half of all the carbon dioxide emitted by human activities remains in the ocean today. atmosphere – and it will likely stay there for hundreds of years, influencing the climate on a global scale.

In the first year of the pandemic in 2020, when fewer people were driving and some industries briefly shut down, carbon dioxide emissions from fuels fell by about 6%. But this did not prevent the increase in the concentration of carbon dioxide because the amount released into the atmosphere by human activities far exceeded what nature could absorb.

If civilization today ceased its carbon dioxide emission activities, it would take several hundred more years for the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to decline naturally enough to restore the equilibrium of the carbon cycle of the planet due to the long lifespan of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. .

How do we know greenhouse gases can change the climate

There is ample scientific evidence to indicate that the increase in greenhouse gas emissions over the past century and a half is a driver of long-term climate change around the world. For example:

-

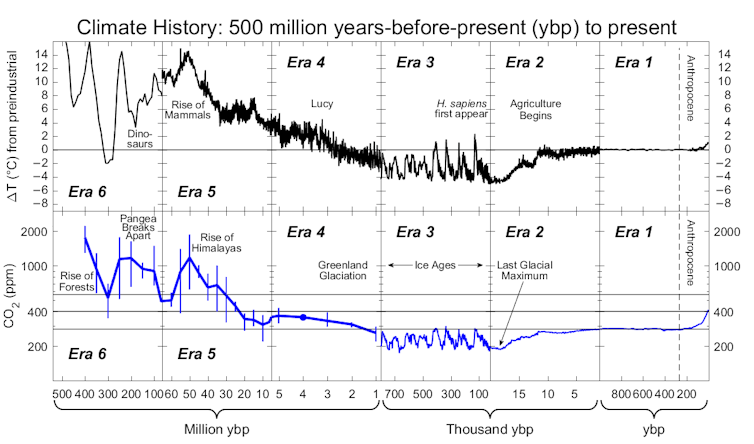

Long-term records from ice cores, tree rings and corals show that when carbon dioxide levels are high, temperatures are also high.

-

Our neighboring planets also offer evidence. Venus’s atmosphere is thick with carbon dioxide, and it is therefore the hottest planet in our solar system, even though Mercury is closer to the sun.

Temperatures are rising on all continents

The rise in temperatures is evident in records from all continents and over oceans.

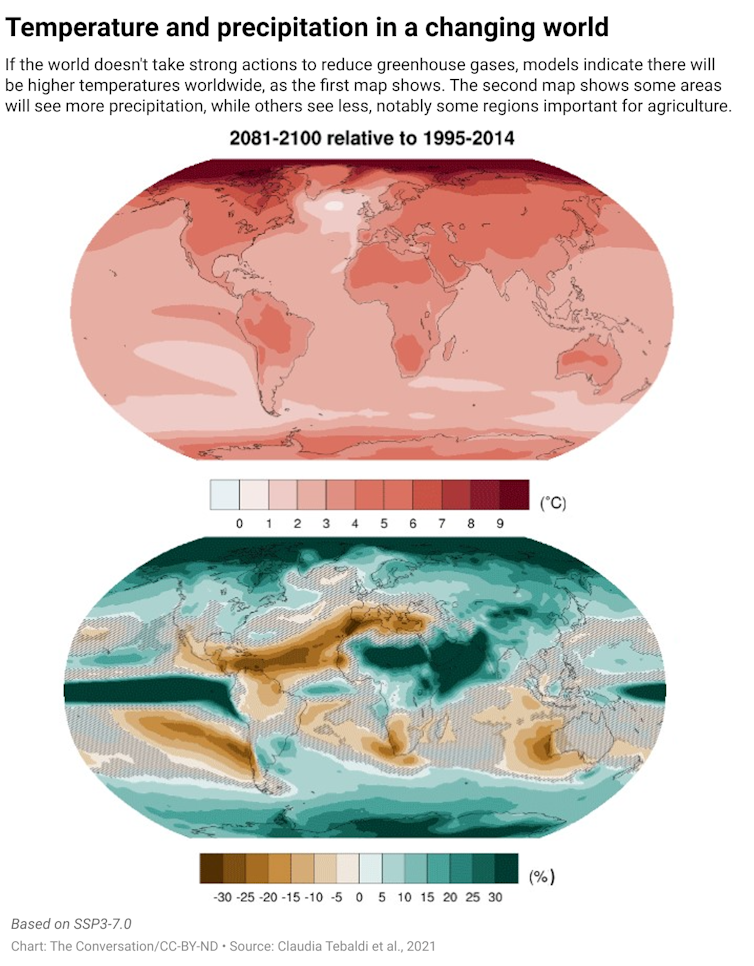

However, temperatures are not rising at the same rate everywhere. Various factors affect local temperatures, including land use which influences the amount of solar energy absorbed or reflected, local heating sources such as urban heat islands and pollution.

The Arctic, for example, is warming about three times faster than the global average, in part because as the planet warms, melting snow and ice makes the surface more likely to absorb, rather than reflecting, solar radiation. As a result, snow cover and pack ice recede even faster.

What climate change is doing to the planet

Earth’s climate system is interconnected and complex, and even small changes in temperature can have large impacts – for example, with snow cover and sea level.

Changes are already underway. Studies show that rising temperatures are already affecting precipitation, glaciers, weather conditions, tropical cyclone activity and severe storms. A number of studies show that the increase in the frequency, severity and duration of heat waves, for example, affects ecosystems, human lives, trade and agriculture.

Historical records of ocean water levels have shown mostly consistent increases over the past 150 years as glacial ice melts and rising temperatures raise ocean water, with some local variations due to the sinking or elevation of land.

While extreme events are often due to complex sets of causes, some are exacerbated by climate change. Just as coastal flooding can be made worse by rising sea levels, heat waves are more damaging with higher reference temperatures.

Climate scientists are working hard to estimate future changes resulting from increased carbon dioxide and other expected changes, such as the world’s population. It is clear that temperatures will rise and precipitation will change. The exact magnitude of the change depends on many interacting factors.

Some reasons for hope

On a note of hope, scientific research is improving our understanding of the climate and the complex earth system, identifying the most vulnerable areas and guiding efforts to reduce the drivers of climate change. Work on renewables and alternative energy sources, as well as on ways to capture carbon from industries or the air, offers more options for a better prepared society.

At the same time, people are learning how they can reduce their own impact, with the growing understanding that a globally coordinated effort is needed to have a meaningful impact. Electric vehicles, as well as solar and wind power, are expanding at previously unthinkable rates. More and more people are showing a willingness to adopt new strategies to use energy more efficiently, consume more sustainably and choose renewable energies.

Scientists increasingly recognize that moving away from fossil fuels has additional benefits, including improved air quality for human health and ecosystems.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]![]()

Betsy Weatherhead, Senior Scientist, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We are a voice for you; you have been a great support to us. Together, we are building independent, credible and courageous journalism. You can help us more by making a donation. It will mean a lot to our ability to bring you news, insights and analysis from the field so that we can make changes together.

[ad_2]