Billions of dollars could be misallocated to tackle the wrong climate threats around the world because the models used by central banks and regulators are not fit for purpose, a leading Australian climate researcher has said.

Prof. Andy Pitman, director of the Australian Research Council’s Center of Excellence for Climate Extremessaid regulators relied on models that can predict how average climates will change as the planet warms, but were less likely to be helpful in predicting how extreme weather will set jeopardize individual localities such as cities.

Concerns, detailed in a report in the journal Environmental Research: Climatewere highlighted by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s Monday publication of its 2022-23 business plan. Apra plans to “continue to ensure that regulated institutions are well prepared for the risks and opportunities presented by climate change”.

But Pitman said regulators were still ill-equipped to assess risk and regulate the ability of banks and other institutions to deal with it.

“Without a shadow of a doubt, we are overestimating the cost of climate change in some regions and grossly underestimating it in others,” Pitman said. “We need to take this issue seriously – not just access the information that’s floating around and think we can put it together to make proper economic assessments.”

Sign up to receive the best stories from Guardian Australia every morning

“If you’re going to throw away billions or trillions of dollars, you have to make sure you’re getting the right scientific advice on how to interpret climate information,” he said. “I think it’s obvious, but [regulators] don’t do that.

Pitman’s article, and another he co-wrote for Nature Climate Change in 2021, looked at models used by groups such as Network for Greening the Financial System. The NGFS advises around 100 central banks and other regulators around the world, including the Reserve Bank and Apra of Australia.

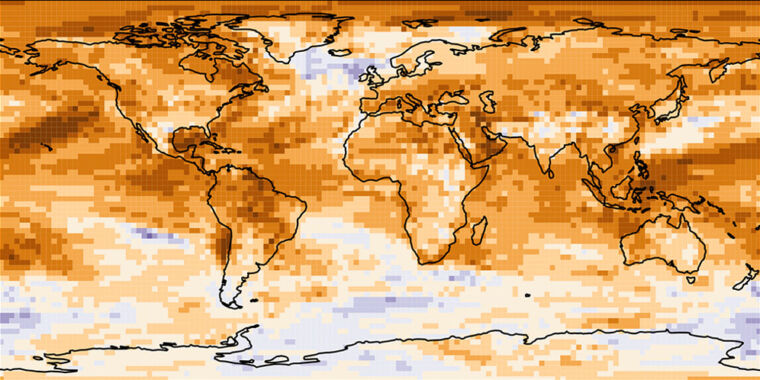

However, the climate models that underpin this advice are based on general climate change, such as rising temperatures. Partly because their resolution typically only covers 100km by 100km regions, the coarseness of the models makes them unreliable for predicting how extreme weather events will change, Pitman said.

Without their own climatologists, the RBA and Apra rely on scenarios generated by the NGFS to understand how a warming planet will influence economic and financial stability.

The RBA referred the questions to Apra, where a spokesperson said: ‘Apra’s objective is not to specify individual climate risks for different regulated entities, but rather to ensure that entities take lending, investment and underwriting decisions based on a comprehensive understanding of relevant risks, including climate risks.

“We do not assess risk on behalf of the entities we regulate,” the spokesperson said.

Apra recently published the results of a self-assessment survey on the members’ approach to these risks. It is also completing its first assessment of the climate vulnerability of the five main banks.

Pitman, who had contributed to the soon-to-be-released inquiry into the New South Wales floods earlier this year, said the standard approach is to avoid being complacent about possible changes that might not be well understood.

For example, people should not build on floodplains, even though the trend of future climates may cause some areas to receive fewer, but more short-term, intense, multi-day rainfall events.

Decisions needed to be “framed in a deep understanding of uncertainty and chosen very carefully so as not to harm” and include greater investment in science, Pitman said.

He said Apra’s business plan involved “we can do this well and we will continue to do this well, and I think that’s brave”.

For example, it was clear that the flood-prone Hawkesbury River near Sydney would flood “again and again and again”, Pitman said.

“You don’t need climate projections to say there’s vulnerability there,” he said. “Go look where there are vulnerabilities in supply chains, or in planning for those most at risk, and invest in those because you’re on very sure ground that those risks don’t go away. “