[ad_1]

The long-awaited new report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is due later today. Prior to publication, a debate erupted over the computer models at the heart of global climate projections.

Climate models are one of the many tools that scientists use to understand how the climate has changed in the past and what it will do in the future.

A recent article in the eminent American magazine Science questions the way in which the IPCC will treat certain climate models which “heat upâ€. Some models, he said, have projected rates of global warming “that most scientists, including model makers themselves, think are blazingly fast.”

Read more: Monday’s IPCC report is very important for climate change. So what is it? And why should we trust him?

Some commentators, including in Australia, interpreted the article as proof that climate modeling had failed.

So should we use climate models? We are climatologists at the Australian Center of Excellence for Climate Extremes, and we believe the answer is a definite yes.

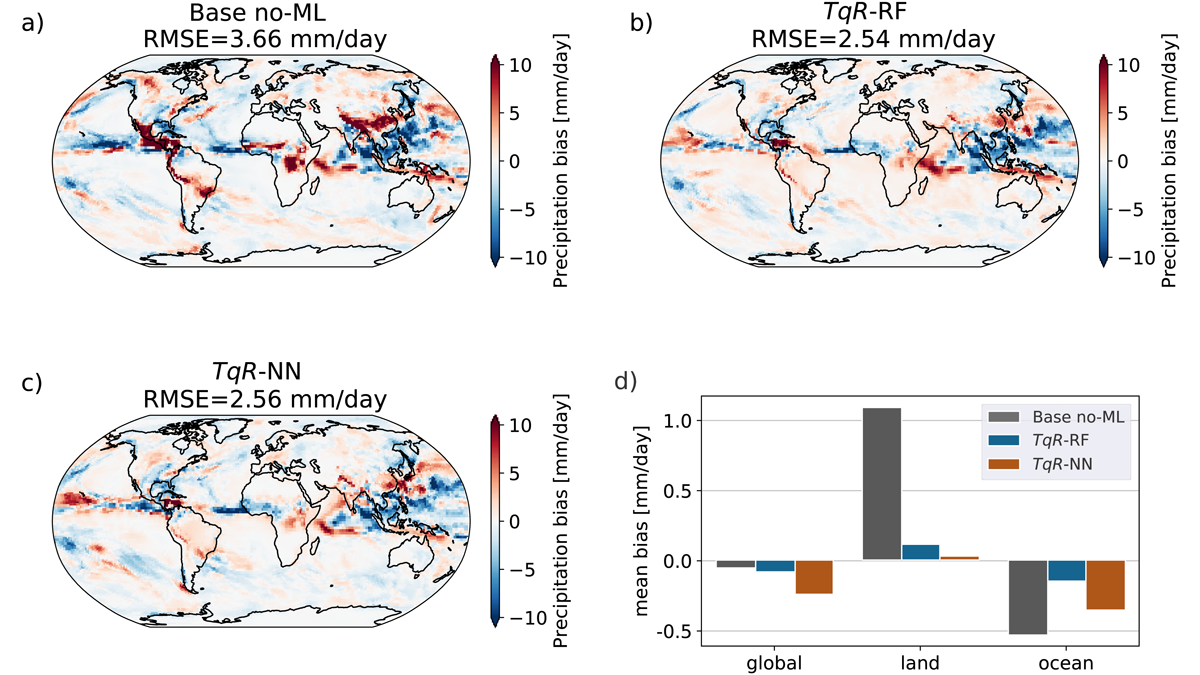

Our research uses and improves climate models so that we can help Australia cope with extreme events, now and in the future. We know when climate models are hot or cold. And identifying an error in some climate models doesn’t mean the science has failed – in fact, it means our understanding of the climate system has advanced.

So let’s see what you need to know about climate models before the IPCC conclusions.

EPA / YANNIS KOLESIDIS

What are the climate models?

Climate models include millions of lines of computer code representing the physics and chemistry of the processes that make up our climate system. The models run on powerful supercomputers and have simulated and predicted global warming with remarkable accuracy.

They show unequivocally that the global warming since the industrial revolution is due to the emissions of greenhouse gases of human origin. This confirms our understanding of the greenhouse effect, known since the 1850s.

The models also show that the intensity of many recent extreme weather events around the world would be essentially impossible without this human influence.

Scientists do not use climate models in isolation or without considering their limitations.

In recent years, scientists have known that some new generation climate models are likely to overestimate global warming, and others underestimate it.

This awareness is based on our understanding of Earth’s climate sensitivity – by how much the climate will warm when the levels of carbon dioxide (COâ‚‚) in the atmosphere double.

Before the industrial age, levels of COâ‚‚ in the atmosphere were 280 parts per million. Thus, a doubling of COâ‚‚ will occur to 560 parts per million. (For context, we’re currently at around 415 parts per million).

The latest scientific evidence, using observed warming, paleoclimatic data, and our physical understanding of the climate system, suggests that global average temperatures will most likely increase by 2.2 ℃ to 4.9 ℃ if CO₂ levels double.

The vast majority of climate models operate within this climate sensitivity range. But some don’t – instead suggesting an increase in temperature as low as 1.8 ℃ or as high as 5.6 ℃.

It is believed that the biases of some models come from representations of clouds and their interactions with aerosol particles. Researchers are starting to understand these biases, gain a better understanding of the climate system, and further improve models in the future.

With all of this in mind, scientists use climate models with caution, giving more weight to climate model projections that are consistent with other scientific evidence.

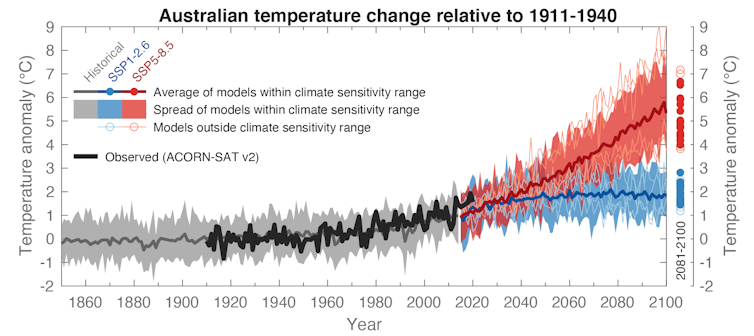

The following graph shows how most models fall within the expected climate sensitivity range – and whether some are running a little hot or cold doesn’t change the overall picture of future warming. And when we compare the model results with the warming we’ve already seen in Australia, there’s no indication that the models are overcooking things.

What does the future look like?

Future climate projections are produced by giving models different possibilities for greenhouse gas concentrations in our atmosphere.

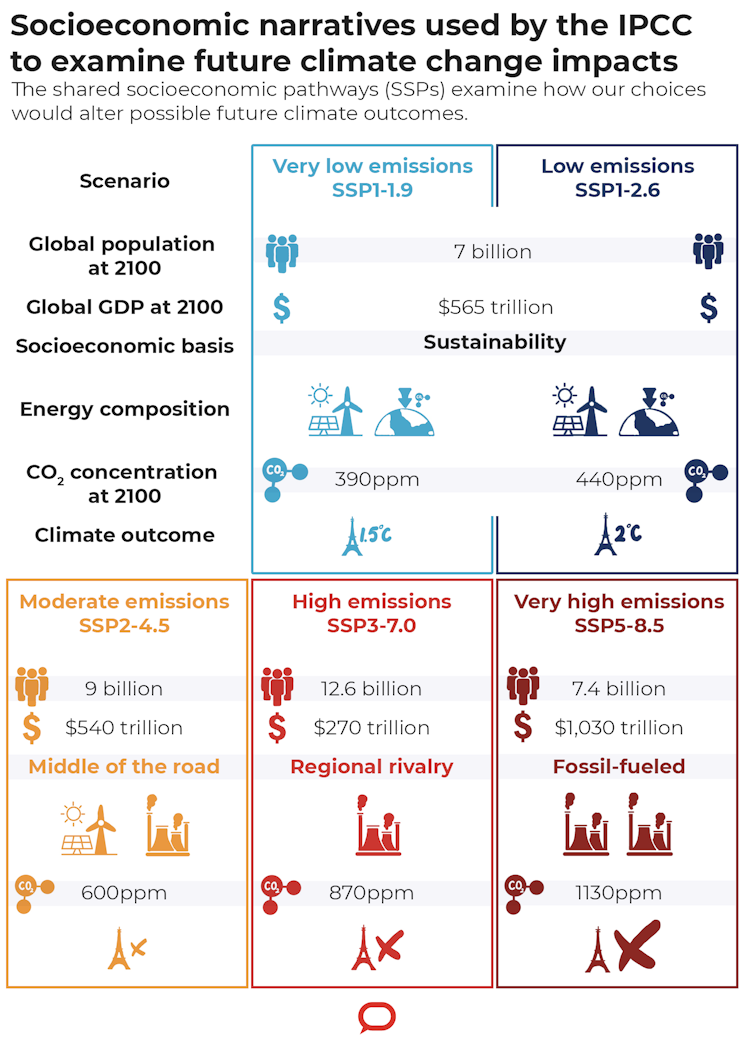

The latest IPCC models use a set of possibilities called “shared socio-economic pathways†(SSP). These pathways correspond to expected population growth, and where and how people will live, with plausible levels of atmospheric greenhouse gases that would result from these socio-economic choices.

Pathways range from low-emission scenarios which also require significant removal of atmospheric COâ‚‚ – giving the world a reasonable chance of meeting Paris Agreement targets – to high-emission scenarios where temperature targets are largely exceeded. .

Nerilie Abram, according to Riahi et al. 2017, CC BY-ND

Before the IPCC report, some say the high-emission scenarios are too pessimistic. But similarly, one could argue that the lack of climate action over the past decade, and the lack of technology to remove large volumes of COâ‚‚ from the atmosphere, mean that low-emission scenarios are overly optimistic.

If countries meet their existing emission reduction commitments under the Paris Agreement, we can expect to be somewhere in the middle of the scenarios. But the future depends on our choices, and we should not dismiss any path as implausible.

It is very important to know both the future risks to avoid and what is possible with ambitious climate action.

Read more: The climate won’t heat up as much as we feared – but it will heat up more than we hoped

Unsplash

Where from here?

The IPCC report can be expected to be deeply worrying. And sadly, the 30-year history of the IPCC tells us that the findings are more likely to be too conservative than too alarmist.

A huge global effort – both scientific and computational – is needed to ensure that climate models can provide even better information.

Climate models are already phenomenal large-scale tools. But increasingly, we will need it to produce small-scale projections to help answer questions such as: where to plant forests to mitigate carbon? Where to build flood defenses? Where could crops best be grown? Where would renewable energy resources be best located?

Climate models will continue to be an important tool for the IPCC, policymakers and society as we attempt to manage the inevitable risks to come.

[ad_2]