UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — One size doesn’t always fit all, especially when it comes to global weather patterns, according to Penn State climate researchers.

“The impacts of climate change rightly concern policy makers and stakeholders who need to make decisions about how to deal with climate change,” said Fuqing Zhangprofessor of meteorology and director, Center for Advanced Data Assimilation and Predictability Techniques, Penn State. “They often rely on regional and local scale climate model projections in their decision-making.”

Zhang and Michael MannEmeritus Professor of Atmospheric Sciences and Director, Earth System Science Center, were concerned that direct use of climate model results at local or even regional scales would produce inaccurate information. They focused on two key climate variables, temperature and precipitation.

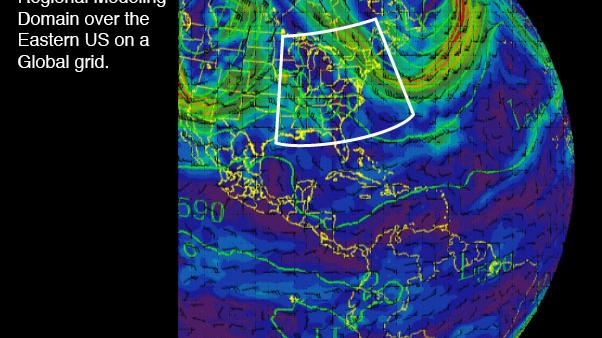

They found that projections of temperature changes with global climate models became increasingly uncertain at scales less than about 600 horizontal miles, a distance equivalent to the combined widths of Pennsylvania, Ohio and Indiana. . While climate models could provide useful information about expected global warming, for example, for the Midwest, predicting the difference between Indianapolis and Pittsburgh warming might prove futile.

Regional precipitation changes were even more difficult to predict, with estimates becoming highly uncertain at scales less than about 1,200 miles, which equals the combined width of all states from the Atlantic Ocean to New Jersey to Nebraska. . The difference between the evolution of total precipitation in Philadelphia and Omaha due to global warming, for example, would be difficult to assess. The researchers report the results of their study in the August issue of Advances in Atmospheric Sciences.

“Decision makers and stakeholders use the information from these models to inform their decisions,” Mann said. “It’s crucial that they understand the limitation of information that model projections can provide at the local scale.”

Climate models provide useful predictions of global warming of the planet and larger-scale changes in precipitation and drought patterns, but are much more difficult to predict, for example, whether New York City will become wetter or drier, or coping with the effects of mountain ranges like the Rocky Mountains on regional weather patterns.

“Climate models can significantly project global warming, sea level rise and very large-scale changes in precipitation patterns,” Zhang said. “But they are uncertain of the potential significant ramifications on society in a specific location.”

The researchers believe that further research could lead to a reduction in uncertainties. They caution users of climate model projections to consider the increased uncertainties in evaluating local climate scenarios.

“Uncertainty is hardly a reason for inaction,” Mann said. “Furthermore, uncertainty can go both ways, and we need to be aware of the possibility that impacts in many regions could be significantly larger and more costly than climate model projections suggest.”

Also working on this project, Wei Li, a former postdoctoral fellow at Penn State now at NOAA/NWS/NCEP/Environmental Modeling Center, College Park, Md.

The National Science Foundation and the Office of Naval Research supported this work.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gray/HAQHVR4PTFEPFIE77LUEQ2PR7I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gray/HAQHVR4PTFEPFIE77LUEQ2PR7I.jpg)