An aerial view of icebergs and the ice cap near Pituffik, Greenland.

Kerem Yucel/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Kerem Yucel/AFP via Getty Images

An aerial view of icebergs and the ice cap near Pituffik, Greenland.

Kerem Yucel/AFP via Getty Images

During Earth’s ice ages, much of North America and northern Europe was covered in massive glaciers.

About 20,000 years ago, these ice caps began to melt rapidly, and the resulting water had to go somewhere, often under the glaciers. Over time, massive valleys formed under the ice to drain water from the ice.

A new study of how glaciers melted after the last ice age could help researchers better understand how today’s ice caps might react to extreme heat resulting from climate change, study authors say. .

The study published this week in Quaternary Science Reviewshelped clarify how — and how quickly — these channels formed.

“Our results show, for the first time, that the most important mechanism is probably the summer melting at the ice surface which makes its way to the bed through cracks or chimney-like conduits and then flows under pressure from the ice sheet to cut the channels,” said Kelly Hogan, co-author and geophysicist with the British Antarctic Survey.

Researchers have discovered thousands of valleys under the North Sea

By analyzing 3D seismic-reflection data originally collected as part of risk assessments for oil and gas companies, researchers have discovered thousands of valleys across the North Sea. These valleys, some of which date back millions of years, are now deeply buried under the mud of the seabed.

Some of the canals were enormous – as large as 90 miles wide and three miles wide (“several times larger than Loch Ness,” the UK-based research group noted).

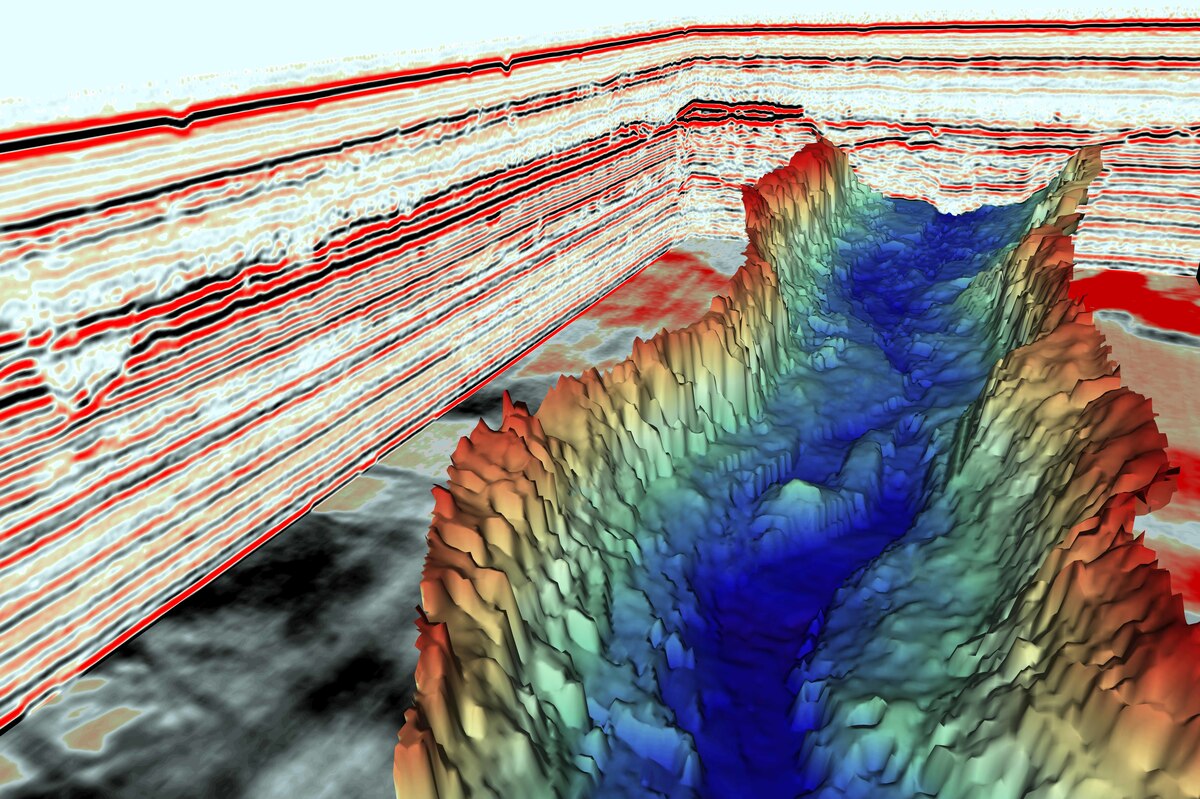

A digital model of a massive channel that transported meltwater away from ancient glaciers.

James Kirkham/British Antarctic Survey

hide caption

toggle caption

James Kirkham/British Antarctic Survey

A digital model of a massive channel that transported meltwater away from ancient glaciers.

James Kirkham/British Antarctic Survey

What surprised the researchers the most, they said, was how quickly these valleys formed. When the ice melted rapidly, the water carved out the valleys over hundreds of years – lightning fast, in geological terms.

“This is an exciting finding,” said lead author James Kirkham, a researcher at BAS and the University of Cambridge. “We know that these dramatic valleys are carved out during the agony of the ice caps. Using a combination of state-of-the-art subterranean imaging techniques and a computer model, we learned that tunnel valleys can be eroded rapidly beneath the ice sheets experiencing extreme heat,”

Meltwater channels are traditionally thought to stabilize melting glaciers and, by extension, sea level rise, by helping to cushion the collapse of ice sheets, researchers said.

New findings could complicate this picture. But the speed at which the channels formed means their inclusion in current models could help improve the accuracy of predictions about the current melting of the ice sheet, the authors added.

Today, only two large ice caps remain: Greenland and Antarctica. The rate at which they melt is likely to increase as the climate warms.

“The critical question now is whether this ‘additional’ flow of meltwater through the channels will cause our ice sheets to flow faster or slower into the sea,” Hogan said.