After spending nearly a decade working in computer science and artificial intelligence (AI), Sasha Luccioni was ready to uproot her entire life three years ago after becoming deeply concerned about the climate crisis.

But her partner convinced her not to give up on her career altogether, but instead to apply her AI knowledge to some of the challenges posed by climate change.

“You don’t have to quit your job in AI to help tackle the climate crisis,” she said. “There are ways in which almost any AI technique can be applied to different parts of climate change.”

She joined Montreal-based artificial intelligence research center Mila and became a founding member of Climate Change AI, an organization of volunteer academics advocating for the use of AI to solve related problems. to climate change.

Luccioni is part of a growing community of researchers in Canada who are using AI in this way.

In 2019, she co-wrote a report arguing that machine learning can be a useful tool in mitigating and adapting to the effects of climate change.

Computer scientists define machine learning as a form of artificial intelligence that allows computers to use historical data and statistical methods to make predictions and decisions without having to be programmed to do so.

Common applications of machine learning include predictive text, spam filters, language translation applications, streaming content recommendations, malware and fraud detection, and social media algorithms.

According to the 2019 report, applications of machine learning in climate research include climate prediction and optimization of electricity, transportation and energy systems.

Preparing for crop diseases

Researchers at the University of Prince Edward Island (UPEI) are using AI modeling to warn farmers of risks to their crops as the weather becomes more unpredictable.

“If you have a dry year you see very little disease, but with a wet year you can get a lot of disease around the plants,” said Aitazaz Farooque, acting associate dean of the School of Climate Change and adapting UPEI.

Researchers can feed weather data from previous years into an AI model to predict the type of diseases that could compromise crops at different times of the year, Farooque said.

“Then the producer can be a bit proactive and figure out what they’re getting into,” he said.

WATCH | Take a look at UPEI’s School of Climate Change and Adaptation:

From drones to dormitories, St. Peter’s Bay’s state-of-the-art research facility will host world-class students and researchers studying the many facets of climate change.

Agriculture in Prince Edward Island is primarily rain-fed, and providing farmers with more accurate rainfall forecasts can also help them achieve better yields, Farooque said.

“With climate change, we see different trends where the total cumulative precipitation doesn’t change much, but the timing is important,” he said.

“If this does not happen at the right time, the sustainability of our agriculture can be threatened.”

Study behavior in adverse weather conditions

Another application of AI is being studied at McGill University, where researchers are using historical and recent weather data to predict the social impacts of extreme weather events that are affected by climate change, such as heat waves. , droughts and floods.

According to Renee Sieber, an associate professor in McGill’s Department of Geography, researchers hope to find out how people have reacted to disruptive weather events in the past and if that can teach us anything about our resilience in the future.

The team will use a form of AI called natural language processing to analyze social narratives related to weather events in newspapers and other media.

“AI is very good at organizing, synthesizing, finding patterns or sentiment from large amounts of unstructured text,” Sieber said.

“Basically what you’re doing is throwing newspaper articles into a bucket, and you see what comes out.”

Sieber said his team will take results from previous articles and today’s social media and compare them to corresponding weather records to identify people’s responses to weather events over time.

The recordings of the McGill Observatory are the longest and most detailed uninterrupted written records of weather patterns in Canada and contain a massive amount of information, Sieber said. Weather recording began there in 1863 and continued until the 1950s.

“These data are the only direct measure of climate change we have. [in Canada]”, Sieber said.

Optimize energy consumption

Some Canadian companies are using AI to minimize waste and build more energy-efficient infrastructure.

Scale AI, a Montreal-based investor group that funds supply chain-related projects, has worked with grocery chains such as Loblaws and Save-on-Foods to identify buying habits. Thanks to AI, companies are able to better forecast demand and less food is wasted, said Julien Billot, CEO of Scale AI.

“Every optimization we can achieve improves the resilience of supply chains and contributes to the use of fewer resources,” she said.

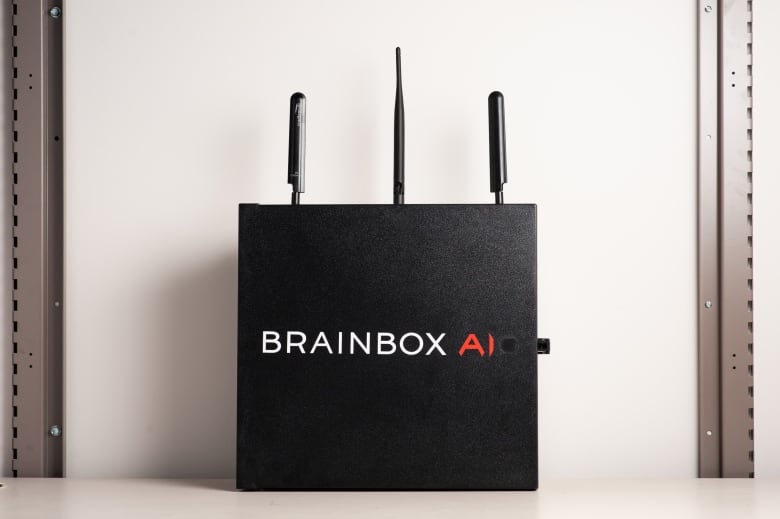

Another Montreal company, BrainBox Al, focuses on improving energy efficiency by optimizing HVAC systems in commercial buildings.

The machine learning technology is contained in a 30cm wide box that connects to a building’s HVAC system. It raises or lowers temperatures based on data inputs such as weather forecasts, utility prices, and carbon emissions calculations.

The system was able to reduce the energy consumed by some HVAC systems by 25%, said BrainBox CEO Sam Ramadori, and within two years the company had installed the technology in 350 buildings in 18 countries.

“The same type of intelligence that we bring to buildings probably has an infinite number of applications. Just pick a sector,” Ramadori said.

“How we make cement, how we ship goods – all of this needs to be made more efficient over time as part of the fight against climate change.”

According to Ramadori, BrainBox AI is working on technology that will allow buildings to connect to each other and communicate with energy networks through the company’s cloud server.

This has the potential to minimize energy waste city-wide, as energy networks more accurately detect where and when electricity is needed, he said.

“The power grid can say, ‘Hey, the next two hours are going to be busy. I need you to find a way to reduce consumption.’ And with the AI brain on top, it’s able to say, “OK, I can scale down a little here and a little there. I got you covered,” Ramadori said.

Fairness Limits to AI

Access to the kind of AI that can help solve climate-related problems is not equal across the world.

Wildfires in North America, for example, tend to get more attention from developers than locust infestations in East Africa, said David Rolnick, an assistant professor of computer science at McGill. and member of Mila.

“How climate change affects a community varies greatly between different geographies,” said Rolnick, who is also president of Climate Change AI.

AI technology relies on datasets, and many communities don’t have access to enough robust data needed to create machine learning algorithms, Rolnick said.

In Canada, some Indigenous and remote northern communities still face significant digital divides compared to other parts of the country, he said.

“Working to democratize this is fundamentally important,” Rolnick said.

Rolnick co-wrote a study last year outlining various limitations to the implementation of AI for climate change solutions in Canada. He called for increased funding for AI research and more AI education in primary and secondary education, as well as standards and protocols for sharing data related to climate projects.

Rapidly implementing large-scale AI literacy programs for policymakers and leaders in climate-related industries could help “demystify” AI, the report says.

“We often see a lack of relevant knowledge, and educational programs can help people understand what these tools can and cannot do,” Rolnick said.